Published: February 11, 2022

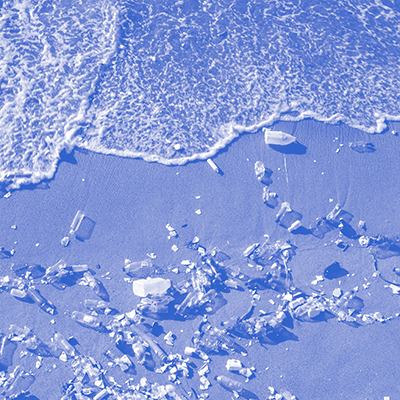

Plastic pollution is a complex and growing global issue, with millions of tons of plastic waste reaching our oceans each year, killing thousands of seabirds, turtles, seals and other marine mammals.

However new research has identified an approach to removing, recycling and reutilizing plastic that not only has a positive impact on the environment, but can also benefit communities in need in developing countries.

Joining me to discuss how supply chain and block chain technology are being leveraged in innovative new ways to address the issue of plastic pollution is Opher Baron with the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management.

So, when there is more value here, you and I are willing to put some money to reducing our own personal plastic footprint. There are companies that are willing to become, that want to become, ‘plastic neutral’ and they are willing to put money and invest into it.

Interviewed this episode:

Opher Baron

University of Toronto

Opher Baron is a Distinguished Professor of Operations Management and the Academic Director, MMA Program at the Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto. He was a visiting associate Professor at the Industrial engineering and Management faculty of Technion (2009/10) and a visiting Professor at the School of Information Management and Engineering, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics (2016/17). He has a PhD in Operations Management from the Sloan School of Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and an MBA and BSc in Industrial Engineering and Management from The Technion – Israel Institute of Technology. On the teaching front, Opher is especially proud of the modeling and analytics courses he introduced and teaches at Rotman. On the application front he is proud of launching the Covidppehelp.ca platform with his colleagues. This platform has facilitated the flow of millions of PPE items to end-user customers during the global Covid19 pandemic. His research interests include queueing, business analytics, service operations (such as healthcare), autonomous vehicles, and revenue management. Opher’s work is published in leading journals such as Operations Research, and Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, and he has won several research and teaching awards and grants, including the 1000 Talents Plan Scholar from the Shanghai Municipal Government, 2017. Opher is active in the operations research and operations management community. He has given numerous invited keynote lectures and seminars, chaired several conferences, clusters, and sessions, and is currently serving on the advisory board and editorial boards of several journals.

Episode Transcript

Ashley Kilgore:

Plastic pollution is a complex and growing global issue with millions of tons of plastic waste reaching our oceans each year, killing thousands of sea birds, turtles seals, and other marine mammals. However, new research has identified an approach to removing recycling and re-utilizing plastic that not only has a positive impact on the environment, but can also benefit communities in need in developing countries. Joining me to discuss how supply chain and blockchain technology are being leveraged in innovative new ways to address the issue of plastic pollution is Opher Baron with the university of Toronto’s Rotman school of management. Opher it’s such a pleasure to speak with you. I’m so excited to dive into the incredible work that you’re doing.

Opher Baron:

Thank you very much. I’m excited to be here and talk with you about it. Thanks for inviting me over.

Ashley Kilgore:

Opher to start, can you paint a picture of the true magnitude of the amount of plastic waste entering our oceans?

Opher Baron:

Yes, but first I want to know that this is based on a joint work with my colleagues Gonzalo Romero here from Rotman and Sean Ju from Chinese university in Hong Kong, as well as with Sean’s PhD student Judo Zheng. And going back to your question, there is about 30 million tons of plastic waste or 10% of the world’s annual plastic production that is reaching the ocean every year. I wanted to draw a more visual picture of this. So we’ll have a sense of that. So if you think about a large cement truck, those are 30 tons tracks, but obviously cement is a little bit denser and heavier than plastic by about 20 times.

Opher Baron:

So if you do this calculation together, you see about 600 million trucks pouring plastic into the ocean every year. You want to translate this to trucks per second, it’s about two trucks every second, all are basically throwing plastic into the ocean. Think about the, how great of operations we created that can bring two trucks a second to spill all of these plastic into the oceans. Obviously it’s a shameful operation, but just to give a sense of the magnitude of the problem. Now, to talk a little bit more about this in the context of plastic that reaches the oceans, there are some estimates that about 80% of this plastic is flowing from developing coastal countries.

Opher Baron:

And this is an important thing to consider in what we’ll talk a little bit later today about how some innovative business models can help reduce ocean bound plastic, and increase its recycling. Before I let you ask your next question, I want to give a little bit, additional perspective on the implications of pouring so much plastic into the ocean. If we continue with the same rate, there are predictions that by 2050, there’s going to be more plastic than fish in our oceans. So this is just an incredible amount of garbage that we put into our oceans from which we eat a lot and I will end it at that.

Ashley Kilgore:

And so as this issue of plastic pollution is obviously a growing one. We’re seeing more and more attention paid to and emphasis placed on the importance of reducing and recycling. Not only on the individual level with things like reusable water bottles and metal straws, but for organizations as well to become what is known as plastic neutral. Can you give us some background on what this means?

Opher Baron:

Yeah, that’s a great question. So the main idea behind this issue of plastic neutrality is to create some circular economy for plastic, but in contrast to what people may often think about the circular economy, it’s not just being able to recycle and reuse plastic. The entire process behind this creating a better circular economy for plastic includes some other steps. And the main part of them is for example, reducing the usage of unnecessary plastic in packaging, for example, right? So the latest and greatest example I have, you think about my favorite Mars bar, which is being now packaged in some nylon or plastic material. And recently they’re moving into packaging, their bars in paperbacks essentially. So this is reducing consumption and the usage of unnecessary plastic in packing.

Opher Baron:

There are other things that we can do in general in improving the design of the products and the design of packaging a product to reduce plastic consumption in them, as well as to allow to better operate the reverse logistic and supply chain of collecting this plastic and using it again. So, if you use a specific plastic in a large machinery and it’s stuck in the middle of the machinery, I will never be able to recycle it for example, right? So if you can design things a little bit better, so plastic will be more easily cut out of this heavy system and you will be able to recycle it, this is something important to do.

Opher Baron:

So designing products, designing packaging in support of backward supply chain or reverse supply chains is something important and improvement like this will allow us to better collect, better reuse and better recycle plastic. There are many companies, NGOs, governmental organizations, and obviously private citizens that wish to reduce their plastic blueprint. And as you said, getting to a plastic neutrality context, there’s involved the collection of activities like in using more recycled plastic. And this also has some additional benefits to the ESG objectives of many organizations when they can come and say, “Hey, we take care of the environment. We use recycled plastic rather than new one.” They have some bonus points over there.

Opher Baron:

When I add a little bit more on top of that, there is more and more push in recent years from activists around the world to have some global agreement or some, UN treaty on how to deal with plastic pollution. So there is, we are all aware of the Kyoto accord discussing greenhouse gas mission and several generations later, what happens with this accord and for the better of worse while those accords have some limitations to them, an important part that they are helping with is bring attention to issues which are of global importance. And with this in mind, possibly having some global agreement on how to reduce plastic consumption in general and plastic pollution and plastic pollution in the ocean in particular will help us to live in a more sustainable earth basically.

Ashley Kilgore:

Now, traditionally, what have been some of the issues that organizations face in trying to reduce their plastic waste?

Opher Baron:

So I think historically the most obvious part is ROI. Plastic has been so cheap that there was little incentive to design products in a way that will reduce plastic consumption. And people and companies, especially in the developed world are, we felt that the current recycling that we are doing is quite effective, so it’s not that bad. However, there is a lot of plastic that is designed to be done in a single, to be consumed in a single usage fashion. And even if I collect it, there’s not much thing that I can do with it. It’s not going to be a useful raw material from someone else to produce with it. And the obvious example are plastic bags, right? I cannot collect plastic bags and reuse them to do anything useful later. This is already kind of the lowest level of plastic that I can use.

Opher Baron:

So if you think a bit back on collection, especially in the context of some developed countries, when you think, oh, I’m doing enough recycling, recycling of plastic is done. It’s not very effective even in those countries. So I looked at some reports in the US, there’s only 35% of plastic that is recycled or compost. Moreover, even plastic that you and I put in the recycle bin, it may end up not really being recycled. Sometimes it’s just too many logistical issues, an inability to differentiate among different plastic types in a cost effective fashion. And sometimes what happens is that this plastic is not being recycled, but is being down cycled. So to some extent it will become a plastic bag, right? It will not become something that I can recycle again. So the recycle process reduce the value of the plastic and make it less useful in the next round.

Opher Baron:

I think in general, the constant pressure on price that we have, and the fact that plastic is so easy and cheap to produce, prevent us from finding better solutions. I think that now with a lot of supply chains, issues and disasters and pandemic, there’s a lot of competitive pressure. So again, people may tend out to use the cheapest solution, which may well be plastic, but because there is more and more awareness of this situation, there is at least in developed countries, much more pressure on ESG and so on to try and reduce plastic consumption.

Opher Baron:

But this is obviously a pressure that exists in a significantly lower fashion in developing countries. So they’re incentives to reduce plastic consumption or to recycle it where even lower. And I think that there is one more issue that is important in the context of organizations that are trying to reduce their plastic footprint is that much of the plastic that we are using is kind of becoming micro plastic, which we cannot really use again, right? It goes into our landfills and goes into the earth, it goes into the ocean, the animals eat it, we have the animals, right? So logistically some of the plastic is just not well suited to be reused as well.

Ashley Kilgore:

So now this is where you and your work come in. Can you tell us about your approach using supply chain and blockchain technology to reduce plastic pollution and help organizations become plastic neutral?

Opher Baron:

Yeah. So first of all I need to acknowledge that it’s not sort of our ideas, it’s not our approach, but whether an approach that has been taken by some innovative organizations around the world, and we were lucky to collaborate with one of them. But again, to remind, as I said earlier, about 80% of the plastic that ends in the ocean goes there via developing coastal communities. In some of these communities, there has been some level of plastic recycling supply chain and some places there wasn’t, but even when such a recycling supply chain existed, it was focused on recycling plastic for local industrial usage. And the value of the recycled plastic was in this sense relatively low, which provided little incentive to collect large quantities, right? So, as I said before, there’s kind of more and more awareness in developing countries about the importance of reducing plastic consumption and pollution.

Opher Baron:

And the idea is to take part of this value and to move it into developing countries. So when there is more value here, you and I are willing to put some money into reducing our own personal plastic footprint. There are companies that are willing to become, that want to become plastic neutral, and they’re willing to put money and invest into it. And the idea is to take this money and this higher value of plastic, which part of it we give because we want to recycle it and we want to reduce the pollution created by plastic. And if we can do this and move this value to developing countries, we can use this higher value to incentivize local collectors and processors and to collect more plastic. So here, the idea is I take money from, “rich people” and I give it to, “poor people.” People in the bottom of the pyramid.

Opher Baron:

And I allow them to get a better source of income that will help them to reduce their poverty level and will also, when they collect plastic, they reduce plastic pollution and plastic pollution especially of ocean bound plastic, which is the main thing we are talking about today. So companies that are doing this need to make sure that they can really tell us and tell the companies that are putting money into this new supply chain that is being created, if you wish, that it’s really effective. And this is where blockchain technology comes into play. The idea of blockchain technology is that it can allow me to make sure that, the $50 that I paid for collection of 84 kilograms of plastic, which is the average consumption of a plastic for a citizen in North America, to be collected is really being collected and is really being collected from an area near a coastal community.

Opher Baron:

So I’m really taking plastic out of the ocean as being plastic neutral. Obviously now, when I’m also helping to reduce poverty, I have higher incentive to put money into this. So there is the, to me, the main trick behind this business model is that it has what we call a triple threat or a triple objective supply chain. First of all, it can be financially sustainable. Second of all, it has positive environmental impact by reducing plastic pollution and plastic pollution into the ocean. And third of all, it has social impact by reducing poverty in developing coastal communities, as I said before.

Ashley Kilgore:

Now, ultimately, what are some of the unique benefits of this approach, including the impact on the environment?

Opher Baron:

So I feel it’s an ingenious approach, right? The combination of improving the environment, improving the society and not needing donations for it is great, right? So this is kind of rather than having a business that does this benefit because people donate money. It does this benefit and it reduced pollution and reduced poverty in a sustainable fashion. So this is to me, a great example of sustainable operations. And when we think about sustainable operations, it should also be sustainable from a financial point of it. It shouldn’t be relying on external income that would go into it, right? So I think it’s just an ingenious way of taking important issues of global structure and bringing a global supply chain that will collect the plastics, pay for local collectors some bonuses, which induces them to collect more. And then also bring this plastic to reuse by large companies in developed countries and reducing their footprint is just amazing.

Ashley Kilgore:

So Opher while today, we’re talking about addressing plastic pollution, could this insight be leveraged to address other types of pollution?

Opher Baron:

This is a great question. And I think that’s probably where much of our ongoing work is. Where we focus much of our ongoing work. I think that there are similar ideas that can be used to improve recycling of additional materials, such as metal and possibly some technological items like cell phone and so on. And possibly even, non-tangible goods such as energy, right? If you can create some energy in your backyard, wind solar, and you can kind of get money for it in a sensible fashion, that is something that, again, we may be able to support, obviously generating this energy in our backyard requires a large investment that many people cannot afford. So the question is, if there is a good way of combining these ideas and help to improve the sustainability and generating some social and environmental positive impact.

Opher Baron:

So the trick is, and we as supply chain experts know this, there is in the details and there is much work to do in tailoring such solutions to new industries. The solution that is currently being implemented for recycling plastic, the blockchain technology, the bonuses structure, the extra benefit that are given to collectors and local processors. It’s not a simple system to manage and extending it to other industries is not going to be simple in this sense.

Ashley Kilgore:

Opher, it’s truly been a pleasure speaking with you and learning about this exciting approach to cleaning up our oceans for generations to come. Are there any final thoughts you’d like to share with our listeners before we wrap up?

Opher Baron:

No. Just wanted to thank you for inviting me here. And I’m thanking for my coworkers. It’s a pleasure to work with them and such important questions and learn some interesting things about how new IT can improve the operations of supply chains and address some of the globally pressing problems. So thank you for having me over.

Ashley Kilgore:

Want to learn more? Visit resoundinglyhuman.com for additional information on this week’s episode and guest. The podcast is also available for downloader streaming from apple podcasts, Google play, Stitcher and Spotify. Wherever you listen, if you enjoy Resoundingly Human, please be sure to leave review, to help spread the word about the podcast. Until next time I’m Ashley Kilgore and this is Resoundingly Human.

Want to learn more? Check out the additional resources and links listed below for more information about what was discussed in the episode.

Leaning on Innovation to Combat Plastic Pollution in Oceans, CUHK Business School